For here have we no continuing city, but we seek one to come. Hebrews 13:14

Pictured just above is a work of the great America artist, Thomas Cole, whose paintings so often depicted his Christian faith. In “The Expulsion from the Garden,” painted around 1828 and now in the Boston Museum of Fine Art, in the Waleska Evans James Gallery (Gallery 236), Cole vividly portrays Paradise on the right, and on the left, into which the first couple are exiled, a hostile world replete with the consequences of their turning from trusting God to going their own way, which was the sin of Adam and Eve. These opposing realms meet near the center of the canvas. Adam and Eve are cast into an abyss marked by blasted trees, desolate rocks, and a world of dark shadows—all representing this present order in the world, despite all our best effort to beautify our situation. But the promise of the Bible from Genesis 3 onwards is that God’s redeeming love—and that alone—can save us, and therein is great hope—and this is the hope of the Christian Gospel. This truth is declared in the quotation from the Epistle to the Hebrews which leads off today’s homily: “For here we have no continuing city,” which is to say, there’s no ongoing home for us here in this world, “but we seek one to come,” that is, this world is not all there is, that there’s hope of another realm that God has prepared for those who love Him, and all are invited to it.

According to the Bible Abraham, whom we meet early-on—in the 12th chapter of the Bible’s first book, Genesis—is a primary example of the life of trusting in God and looking forward to life in the world to come. Here we find depicted a man who, at age 75, was called by God to leave everything—his home, his ties—and go out from there, not knowing where he was going—and he obeyed! He left the city of Ur of the Chaldees and didn’t even know where he was going—God only said, “To a place I will show you.” The text says he went out, “not knowing whither he went.”

Two thousand years after the call of Abraham, Stephen, the first Christian martyr, in the testimony he gave before he was killed, began by rehearsing the key elements of Abraham’s life, for Abraham was considered the father of all those who follow God: “And [God] said unto him, Get thee out of thy country, and from thy kindred, and come into the land which I shall shew thee” (Acts 7:3). He was quoting Genesis 12:1. This is the call in all ages to those who would follow the true and living God. Abraham’s life is so connected to following God that in several places in the Bible God is even called “the God of Abraham” (Exodus 3:13-15).

Still later, also recorded in the New Testament, we see still further how emphatically Abraham was looked upon by the earliest Christians, so many of whom were Jewish, as we see in the Epistle to the Hebrews:

By faith Abraham, when he was called, obeyed by going out to a place which he was to receive for an inheritance; and he left, not knowing where he was going. 9 By faith he lived as a stranger in the land of promise, as in a foreign land, living in tents with Isaac and Jacob, fellow heirs of the same promise; 10 for he was looking for the city which has foundations, whose architect and builder is God. (Hebrews 11:8-10).

Here we see plainly that the early Christians did not regard this world as their home, and such has been the manner of the faithful ever since. Jesus himself had said of his disciples in prayer to his Father, “They are not of the world, even as I am not of the world” (John 17:16).

Even a thousand years before the coming of Christ, King David acknowledged he was in the same situation in which Abraham was found one thousand years still earlier, despite the kingly power to which God had raised him: “Hear my prayer, O LORD, and give ear unto my cry; hold not thy peace at my tears: for I am a stranger with thee, and a sojourner, as all my fathers were” (Psalm 39:12). He understood that believers in the God of the Bible are pilgrims in this world—it is not to be their home; they are “looking for a city whose builder and maker is God.”

Consider, too, how David stood before a gathering of the whole assembly of the people as he prayed for the building of the great Temple in Jerusalem which would be accomplished by his son, Solomon, “For we are strangers before thee, and sojourners, as were all our fathers: our days on the earth are as a shadow, and there is none abiding” (I Chronicles 29:15). David trusted that Solomon would build that famous first temple for God but he knew, as Solomon also understood, that man’s works in this present world are not the end for those who trust in the Maker of heaven and earth, and that building even the most magnificent things are not man’s final purpose; the temple only pointed to man’s real end—communion with God. Indeed, Jesus once said that he was the true temple (John 2:19-22).

While we may have great responsibilities and do remarkable things in this world—even as David and Solomon did—we are not to think this constitutes the whole, or even the main purpose of life. No, in God’s eyes, what matters is how we walk before Him with an eye toward His law of love and toward following him, who is our true temple, savior and eternal king. David knew he was not sovereign, but that God was his father, savior and sovereign. He made great mistakes when he forgot this, but he repented greatly when his sins were made plain, and then truly remembered who he was and that this world and its goods are not, and were not, the main thing about life. Thus we read the conclusion to which David surely repeatedly came: “I am a stranger in the earth: hide not thy commandments from me” (Psalm 119:19).

Of all the men and women of faith in the Old Testament, from Noah to Abraham to David to all the prophets, the author of the Epistle to Hebrews in the New Testament wrote, “These all died in faith, not having received the promises, but having seen them afar off, and were persuaded of them, and embraced them, and confessed that they were strangers and pilgrims on the earth (Hebrews 11:13).

Even Jesus lived as a stranger in the world—though it was made by him (John 1:1-3). The Bible says, “He was in the world, and though the world was made through him, yet the world did not recognize him. He came to his own, but his own did not receive him” (John 1:10-11). And in another place the Scriptures say, “He was despised and rejected” in this world (Isaiah 53:5). And so while in this world Jesus lived in such a way that showed how he was not of it, even as Luke in his Gospel records Jesus saying: “Foxes have holes, and birds of the air have nests; but the Son of man hath not where to lay his head” (Luke 9:58). And in yet another place in the New Testament it says of the followers of God in the Old Testament, “destitute, afflicted, mistreated— of whom the world was not worthy…” (Hebrews 11:37-38).

This is the verdict passed in the Bible on the lives of those who trusted in God, as Abraham did, and all the Old Testament believers—and believers ever since when they truly saw their situation as human beings: “…now they desire a better country, that is, an heavenly: wherefore God is not ashamed to be called their God: for he hath prepared for them a city” (Hebrews 11:16). Believers are on pilgrimage here in this world, even as the Psalmist puts it in his prayer, “Thy statutes have been my songs in the house of my pilgrimage” (Psalm 119:54).

But now think of the pattern established even in the story of the Exodus, when Moses led the Children of Israel out of bondage. They were shown that Egypt, though it was safe in a way, even while they were all slaves there (for it’s true that one can exchange freedom for security), that it was not to be their home. No, it wasn’t to be so any more than this world is meant to be home to those who trust in the God of Abraham. But it is true that here we so easily can become slaves to the idols of power, pleasure, wealth, safety and the desire to be honored by men. And so they were told, on the eve of their liberation—the first Passover when the angel of death came through the land to seal their need to escape the place—they were to be ready to flee the idols of Egypt and to travel quickly out of that land, even if it meant going into the wilderness. Thus the Bible relates how God told them to eat the final meal before their liberation from that world in which they were slaves: “Now you shall eat it in this manner: with your loins girded, your sandals on your feet, and your staff in your hand; and you shall eat it in haste-- it is the LORD'S Passover” (Exodus 12:11).

This was to be the model for all people following the pattern first set by Abraham, of getting out, escaping the delusions of this present world, even as Israel escaped from bondage in Egypt. Like Abraham, the children of Israel left bondage for the trials and risks of freedom to serve God. They, too, went out, like Abraham, “not knowing where they were going.”

They had to trust in God. But we read that those among them who, after many trials in the wilderness, refused to trust God and wanted to return to Egypt, never knew the joy and peace that belonged to those who continued to trust God. In fact, those who wanted to return to Egypt all died in the wilderness and never entered the promised land. Their children, however, trusting God and following Joshua, did enter it. Joshua, their leader, was a type or shadow – a picture – of that greater Joshua, Jesus Christ. Indeed, the English names Joshua and Jesus come from the same Hebrew name.

How, the, as pilgrims and strangers, are believers to live in this world? Our eyes are to be on the Lord, even as Jesus told his disciples, who saw themselves as love slaves of God and not slaves of this world:

Be dressed in readiness, and keep your lamps lit. Be like men who are waiting for their master when he returns from the wedding feast, so that they may immediately open the door to him when he comes and knocks. Blessed are those slaves whom the master will find on the alert when he comes; truly I say to you, that he will gird himself to serve, and have them recline at the table, and will come up and wait on them” (Luke 12:35-37).

Or as Peter, the leader of Jesus’ band wrote after the ascension of Jesus—in his First Epistle, “Therefore, prepare your minds for action, keep sober in spirit, fix your hope completely on the grace to be brought to you at the revelation of Jesus Christ” (I Peter 1:13). Yet we know that no one is really up to the challenge of following Jesus on their own, without the grace and strength only God can give. Even as Paul wrote to the disciples in the city of Philippi long ago:

Brethren, I do not regard myself as having laid hold of it yet; but one thing I do: forgetting what lies behind and reaching forward to what lies ahead, I press on toward the goal for the prize of the upward call of God in Christ Jesus. Let us therefore, as many as are perfect, have this attitude; and if in anything you have a different attitude, God will reveal that also to you (Philippians 3:13-15).

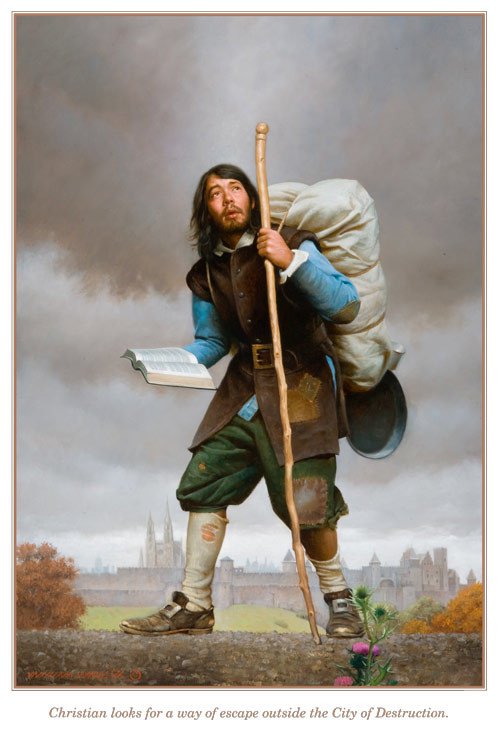

Illustration copyright © 2009 by Michael Wimmer. The Pilgrim’s Progress: From This World to That Which Is to Come (Crossway 2009), 18.

It’s a rough and rugged road, following Jesus, leaving behind what John Bunyan called in his Pilgrim’s Progress “the City of Destruction.”

Taking that road means journeying as a stranger in this world towards God’s city. Human beings cannot get back to the Garden, but God has prepared something even better for those who trust in Him, a Heavenly City in which, above all, they will be with their Savior and Friend forever—with Jesus himself, as we read in Revelation 21 and 22, the last two chapters in the Bible. The thrust of Pilgrim’s Progress is to explain the believer’s life as one of fleeing this world, which is only heading for destruction, and journeying to the Celestial City, bringing along all who are willing to come, too. Bunyan’s Christian, like Abraham, is a model of the sojourning and faithful believer, trusting in God’s grace, knowing that the means to reach that City is not in them; they need a power that is not their own in order to arrive there. They need the power of their big brother, Jesus, who, through God’s loving Spirit, aids them as they travel through a world of trials and temptation, though one not without intimations everywhere of the beauty and goodness of God.

There’s a hymn that speaks of all this and it makes a fitting way to conclude this meditation—“Walking up the King’s Highway” or “Highway to Heaven.” The music and lyrics are by Mary Gardner and Dr. Thomas A. Dorsey, the latter sometimes called “the Father of Gospel Music”:

It’s a highway to heaven.

None can walk up there,

But the pure in heart.

It’s a highway to heaven.

I am walking up the king’s highway.

If you’re not walking,

Start while I’m talking.

Walking up the King’s highway.

There’s joy in knowing

With Him I’m going.

Walking up the King’s highway.

My way gets brighter;

My load gets lighter.

Walking up the King’s highway.

If you be confessing,

There is a blessing.

Walking up the King’s highway.

Christ walks beside me;

His love to guide me.

Walking up the King’s highway.

What makes it possible to walk on that highway? It’s the grace of God expressed in His sending Jesus to pay for our sins on Calvary’s tree, “for God so loved the world that he gave His only begotten Son, that whosoever believes in him should not perish, but have everlasting life” (John 3:16)! He calls out to us, “Come to me, all you that are heavy laden, and I will give you rest” (Matthew 11:28). Thus we’re invited to walk up “the King’s highway”!

God bless you!

~ Paul